Discovering Morgan

Since early in the summer, I’ve been spending one day a week at the Scottish Poetry Library in Edinburgh, digitizing their extensive audio collection. It was a taped interview with Liz Lochhead that tipped me off: it was just after the Wall came down in ’89, and she’d tried to record it in a poem. Could she do it? She wasn’t sure, but – “Eddie could,” she wrote of her companion on the trip: Morgan could.

On my next session at the Scottish Poetry Library, I moved onto the Edwin Morgan tapes. The first was his readings of his poems, interrupted by unedifying commentary by a Scottish academic. Morgan was a good reader, and the poems were good enough. But the full-length interviews were another thing altogether. Here was a Glaswegian in his late 80s, blazing enthusiasm, forward-looking, full of ideas and energy. I checked the ingredients on the packet, but no, Edwin Morgan was the real thing, one of those rare men who forget to fade. Or so I thought at the time.

And this, for me personally, has been the point of Edwin Morgan: beyond the poetry is a bigger message, about the possibilities of life, how it might be possible to negotiate ageing in another way, that the window to the world can and must stay open. It’s a message from an 86 year old man – that’s how old he was at the time of the interview – and this 43 year old man receives it with gratitude. Larkin gave me jazz, and a way of looking at literature that took me out of the academy. But for what? and Morgan, infectiously, seemed to intuit the question and know an answer to it.

Larkin and Morgan: the early years

Edwin Morgan came first, born in 1920, with Larkin following two years later. Both men were products of the prosperous middle class – Larkin’s father was a city treasurer, Morgan’s on the board of a large Glasgow shipbreakers. Morgan was an only child; Larkin had a sister, largely ignored by his biographers. Morgan’s family were staunchly Protestant, and he’d carry something of their anti-Catholic inheritance with him until the 1960s. Larkin’s father had found his own religion, albeit mildly, taking on a modish interest and semi-enthusiasm for pre-War Hitlerism.

Both men were instant wordsmiths – Larkin’s recently published juvenilia is more mature and more extensive than most poets’ final “Collected”. Both, too, had a talent for visual arts. Morgan took drawing and painting seriously, and nearly made a career of it pre-War, whereas Larkin settled on novels and poetry from the outset but littered his letters with winning vignettes and cartoons. It’s interesting how often the poet and the draughtsman exist in the same body: Michelangelo was a capable poet too.

Neither man regarded their childhood with any particular fondness. It’s interesting to compare their childhood photographs:

Morgan would later speak of being punished with silence and the cold shoulder, and of “guilt that can poison life” that is “loath to go away” in The Coals, a poem that also talks, mysteriously, of love and joy treasured “like the fierce salvage of/some wreck that has been built to look like stone/and stand, though it did not, a thousand years.”

Later biographers might want to parse that line for us: it was Morgan’s house, not Larkin’s, that communist literature penetrated, and Larkin’s family, not Morgan’s, who raised eyes to the swastika.

The War

Late in life, Kingsley Amis explained the superiority of 1914-18’s poetry to 1939-45’s on the grounds that the best poets second time around “kept out of it.” Morgan put it differently: you can’t write without solitude, and the War, for which he was called up and duly served, was six years in which he had very little. Morgan, unlike Sidney Keyes or Keith Douglas, was other ranks – an officer could hope for at least some time alone – and even Keyes wrote almost nothing as a soldier.

Larkin’s was a novelist’s war, not a poet’s, best met in his second book “A Girl in Winter”. Morgan’s war poetry came, but not for thirty years: as a writer, he found the War discombobulating (his phrase) and it took him a long time to find his literary feet once more. Then, with the 1970s underway:

At fifty I began to have bad dreams

of Palestine, and saw bad things to come,

began to write my long unwritten war.

I was a hundred-handed Sinbad then,

rolled and unrolled carpets of blood and love,

raised tents of pain, made the dust into men

and laid the dust with men. I supervised

a thesis on Doughty, that great Englishman

who brought all Arabia backin his hard pen. (‘Epilogue’)

For all Larkin’s cynicism, indeed open defeatism, about the War, he himself appears to have been on good form in its early months. Kingsley Amis remembered a brightly dressed, outgoing man, encumbered by a stammer but possessed of outrageous humour and a first class mind unafraid to express itself. Larkin was a pianist and a jazz drummer.. this is a world away from the slowed, ponderous man of only twenty years later that Betjeman met to film his “Monitor” documentary in Hull.

And then one reflects on what Larkin had that Morgan didn’t: Coventry. Larkin travelled home to Coventry a day or two after the first, shocking raid, not knowing if his family would be alive when he alighted from the train. Alone, not surrounded with comrades as Morgan was, he took the long walk through the smoking, shattered streets, and one wonders what that does to a person’s view of themselves, of the future, of the shared nature of the human species.

After Larkin died, Seamus Heaney said that he had lacked “the affirmative impulse” of poetry. It’s not something you’d have heard from Morgan, and there are hints of tensions between the Scotsman and the Irishman. Morgan celebrated instead what he saw as poetry’s freedom – you can write about anything, including the dirt, including the dark, and Larkin was surrounded by both all day in Coventry in 1940.

And in 1941, the music died.

The Music

Jazz was as much Larkin’s first love as poetry: he’d listen to jazz every day until his death. He’d spend his busy 1950s writing poetry, building university libraries from the ground up and reviewing. The reviewing led, eventually, to a Guardian column reviewing jazz, which he did for a decade. It’s not clear, when he began, that he held the views he is now famous for – that jazz died with the arrival of cool and bebop, that the music had described the progress “from Lascaux to Jackson Pollock” in thirty years, that “You have to distinguish between things that seemed odd when they were new but are now quite familiar, such as Ibsen and Wagner, and things that seemed crazy when they were new and seem crazy now, like ‘Finnegans Wake’ and Picasso.â€

But at some point in the early 1960s he noticed that the jazzmen had turned their backs on their audience, physically and mentally: that the record shops were filling up with the output of bands who scowled at the browser as if to say “we’re going to do you, Dad” and that something that had meant youth and life to him was over.

And it seems to have been this point at which Edwin Morgan discovered Brazilian concrete poetry and, at the age of 42, came to creative life.

Of course, Morgan was a gay man in Scotland, and you have to remember that whereas homosexuality was decriminalized in England in 1967, it wouldn’t happen in Scotland until 1980. And the classic “1960s” reached Glasgow only in part – the great tenement clearances, live music. But Morgan was an academic by trade, and the fresh wind blew harder and earlier through the universities than anywhere else.

Morgan found himself at home, culturally, in the 1960s, in a way he had never been before. Larkin, the younger man remember, and also working in a university setting, tangibly began to feel his handhold slipping. It was their response to the very same cultural shifts that sets them apart as men and as artists. Morgan loved the music – his scrapbooks fill with cuttings from New Musical Express and Melody Maker. He loved the new wave of poetry as a live art, and became a marvellous reader of his own work, which would increasingly be written for the ear and not the page. He loved the new forms, of which concrete poetry was only part. And his own poems flowed: two thirds of the best of the Morgan oeuvre date from the same eight years as do the Beatles albums.

For a while, you feel, poetry actually delivered on its promises for Morgan. He could, and did, write about anything – some of his strongest poems from the time were written as science fiction, in an enthusiastic response to the Space Race. So – and it can’t be coincidental – did love: these were his years with John Scott, the love of his life. The drag on Morgan’s creativity that had been World War II had finally lifted, and poetry would never again be as hard for him as it had been in the 1950s.

For Larkin, the great poetic moment had come from within: the point at the end of the 1940s when he abandoned Yeats as his primary influence and turned instead to Auden and Hardy. From then on, it would be Larkinesque poems for twenty strong years, but at no time during that period when Larkin was doing so much for poetry does one feel that poetry was doing anything for Larkin. His poetic loves and enthusiasms were few and, in context, uninteresting: John Betjeman, Gavin Ewart. He encouraged poets who came close to him geographically, like Douglas Dunn, but there is no great worldwide correspondence from Larkin of the type Morgan was famous for.

Instead, as the sixties went on, it’s as if the culture of academia peeled off in one direction, and Larkin, increasingly deaf, increasingly drinking, went another, and whatever one thinks of the 1960s and its own hollow promises, it’s hard not to see Larkin as going off into the dark.

The Notebooks

Betty Mackereth had been Larkin’s “loaf-haired” secretary – her and the hairstyle were both featured from behind in John Betjeman’s 1964 Monitor documentary. She’d be his last mistress, and, in the weeks after his death, took on the task of burning the poet’s notebooks.

Both Larkin and Morgan kept rows of personal notebooks and scrapbooks at home. Both were very aware of their own importance as writers and consequently the importance of a writer’s papers to posterity. Larkin, as librarian, had pioneered the acquisition by British university libraries of writers’ papers, whereas Morgan fed his bit by bit into the Mitchell Library, the Scottish Poetry Library and his own Glasgow University Library.

Larkin left dozens of notebooks: these were not his primary working notebooks for poems (these were separate, and survive) but the recipients of his inner thoughts, diary entries and dreams. It would appear that “Forget What Did”, the poem in which he repeats “Stopping the diary/Was a stun to memory” was either unautobiographical, or a lie, or a feint to some future biographer yet unarrived. Much later, Mackereth recalled the pages she put to the University of Hull furnace: they were very dark, she said, littered with references to black dogs, Nazis, and underground rooms.

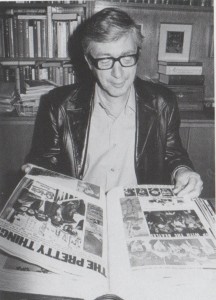

Morgan’s own personal scrapbooks survive unpublished, although he regretted this, having always regarded them as art in their own right and an expression of his own visual artistic expression. Here he is with one of the scrapbooks. One could lose count of the contrasts with Larkin contained in this one photo:

The Working Life

Had Larkin not been a poet, he would still have been one of Britain’s great post-war librarians. Literary Britain might pride itself on its “support” for libraries – witness the stream of authors who have spoken against the recent public library cutback and closures – but behind that thin facade lies a wider landscape of ignorance and condescension. (Librarians have been working for decades on the issues posed by digital formats, email, the web, and digital archiving writ large, and a lot of progress has been made, but you wouldn’t know that from authors on Twitter wailing about Kindles and “real books”).

So what did Larkin do? Kingsley Amis found out by accident:

“I was once sitting behind a newspaper in the (University of) Swansea common room while two engineers, i.e. lecturers in engineering, therefore by common consent philistines, chatted together. One was telling the other about a recent visit to Hull. I pricked up my ears. The chap was full of praise for everything he had seen, ‘especially the library. This fellow Larkin there [neither of the two, clearly, had any idea of what else Philip did] has transformed the place. Oh, a real live wire, myn.‘ When I told Philip this he showed, not the gratification I had unthinkingly expected, but the look of a man whose guilty secret has been revealed.â€

Larkin, as we’ve seen, pioneered the archiving of writers’ private papers by British institutions, providing both the drive and the administrative effort to make it happen.

He was also a great inspiration to his own staff, paying close personal attention to their training and development, running classes in his own spare time and encouraging staff in their efforts to achieve qualifications and development. When computerization came in the 1980s, Larkin was not the man to take it forward, but he had recruited and trained the men and women who did.

Today, the library of the University of Hull is one of the jewels of the British university system, and one of the best libraries built in Britain in the twentieth century.

None of this will be meaningful to the kind of reader who loves libraries in that backward smell-of-old-books way, but Larkin was his father’s son in being a formidable project manager, committee man and builder of institutions.

Morgan was a lecturer in English, remembered well by his students and a man prepared in term time to work into the small hours to keep on top of a heavy workload, but his academic legacy is slight: the poems are what mattered to Morgan, and it’s the poems that matter now.

The Politics

Perhaps the biggest difference between Larkin and Morgan is the simplest: their biographers. Morgan has been written about only by close friends – Hamish Whyte, James McGonigal, Robert Crawford. True, Maeve Brennan, Larkin’s lover and colleague, wrote about their time together and the man who emerges does so with credit. But Larkin’s other biographers have been ideological enemies.

The most obvious of these is Andrew Motion, the man who would later subject Harry Patch, Britain’s last Great War Tommy, to televised humiliation. Martin Amis would summarize Motion’s Larkin biography as a expression of gentle sorrow that Larkin did not – would not! share the unclouded mental health of, for instance, Andrew Motion.

Of course, it’s all about race and right wingery: and in one sense, Larkin did get it wrong where Morgan got it right. There is, there to be recognized even if you happen to share it, an accepted literary political position which you are meant to hold if you value your place at the heart of British literary life. Martin Amis once pointed out that he was less racist than his father Kingsley, and that his sons were less racist than he was himself. Kingsley had been shocked and outraged by attitudes he met in the deep South of the United States, and wondered if the chain would ever be broken.

My own suspicion is that ultimately drink did for both Kingsley Amis and Philip Larkin, and a kind of alcohol-induced depression took hold of both men and coloured their expressions and output after c.1973 that begins to show in the letters, novels and (unpublished) poems.

Morgan himself managed to sidestep the drinking culture, to his great credit (he was dubious about his inclusion in the famous “Milne Poets” painting that also featured McDiarmid, McCaig and the rest of what he described as a “hard drinking crowd”) and, with his sympathy if not support for communism, his politics fitted his literary milieu well. Well enough, indeed, for the one moment that his politics let him down to be all but airbrushed out of history.

In 1987, the Russian poet Irina Ratushinskaya was released from her Siberian prison after five years and allowed to come to the West. She came to London, met the Prime Minister at Downing Street, and embarked on a reading tour of the UK.

She was to have come to Glasgow and share a platform with Edwin Morgan and others – Morgan, a great translator of Russian poetry, was an obvious man to have alongside her. But it never happened: Morgan said no.

He gave the Glasgow Herald a statement of sorts on March 16th 1987:

“I’ve only seen her work in translation and not in the original Russian but it is not impressive. I’m also worried about the political aspect of her appearances. No sooner was she released than she was standing on the doorstep of No.10 having her picture taken and now she’s doing readings for huge fees. Obviously, she’s been badly treated in Russia and I’m sorry for that, but I’ve spoken to one or two people whose business it is to know and as far as I can gather from them, she’s not rated in Russian poetry circles. In fact, she’s a distincty minor poet whose work is not equal to the hype it has received and I would be unhappy to be involved with it.”

One has to bear in mind that this was almost certainly a statement taken down the phone during a call made by the paper without warning which was later polished for effect by an editor, but it still contains odd things.

For one, it conceals the fact that Morgan was a major translator of Russian poetry: he would have been in little need of “one or two people whose business it is to know..” and what, exactly, are “Russian poetry circles” in a Soviet Union in which literature was politically censored and – by Morgan’s own admission – even “minor” poets were “badly treated”.

It can’t have been the “huge fees” that put him off. In 2008, he’d be happy to receive an award of £25,000 from the Borders Art Festival. After his death eighteen months later, it was revealed that his stock market portfolio, developed from shares he’d inherited from family, was worth – and this after the Crash – £1.5 million. Larkin too died a relatively wealthy man who had been able to retire for some time but had refused to abandon his post (courtesy, largely, of his Oxford Book of Modern Poetry) but nothing on the Morgan scale.

And Morgan had appeared on stage with minor poets before. No, this is almost certainly the literary political sensibility at work: Irina’s crime was to go to Downing Street.

The chance to be reminded of the nature of the Soviet regime might not have been welcome either. Interviewed in 1998, Morgan would say,

“I had been to various of these (communist) countries and thought I knew the history reasonably well and I too had thought that the regimes then, by the middle 1980s were still pretty solidly established. I thought perhaps they were going to change bit by bit gradually, there had been little thaws here and there, but I was struck dumb just by what had happened. It was a mixture of feelings: I could understand why the people seemed so glad that they had shaken off the shackles of the Stalinist time; but at the same time I felt like warning them through the television set – do you really know what you’ve done, are you quite sure that it was the right thing to do, do you really know what problems lie ahead for you? I felt this very strongly just because I had hoped so much when I was young, I suppose.”

“Just because I had hoped so much when I was young..” and there’s the reminder that Morgan knew pre-War Glasgow in the grim depression years. After the War, he stayed, and saw things get better – the jobs, the new housing, for that surprisingly brief period (1945 to 1973 is only 28 years, and 28 years ago from the time of writing saw the release of Madonna’s Like A Virgin) and then lived to see it all slowly unravel again at the hands of the people Larkin described as making politics make sense to him for the first time.

Anent jass.

http://archive.org/details/Free_20s_Jazz_Collection

And then Progress occurred.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hSQVvjiXxJU&feature=player_embedded