They cleaned Edinburgh’s buildings many years ago. The odd notable exception, such as that between India Buildings and Edinburgh Central Library, on the difficult turn between Victoria Street and George IV Bridge, only highlights how much has been done. We’re used to them anyway. The eye treats them as scratches in the record and skips on to the next thing.

Last night, however, a walking tour took me inside one of the open caged mausoleums in Canongate Kirk Cemetery. Here, your nose is inches from thick soot that bites deep into the stone, in the same deep pitiless black that the art critic Robert Hughes said he’d seen in the open mouth of death in the moments after his car crash. My guide was yelling intelligent things at the top of his voice, but what I was looking at drove him right out of mind. What, I thought, what the hell could do this?

The answer’s smoke, of course, the same kind of smoke whose eventual removal from the London scene permitted the capital’s mud to return to a genial brown colour. But it’s such an emotionally inadequate word, “smoke”, five letters long and over before you’ve started it. “Smog” is even worse: without the modern suffix “petrochemical” it might be the name of an indulged cat or a soft toy.

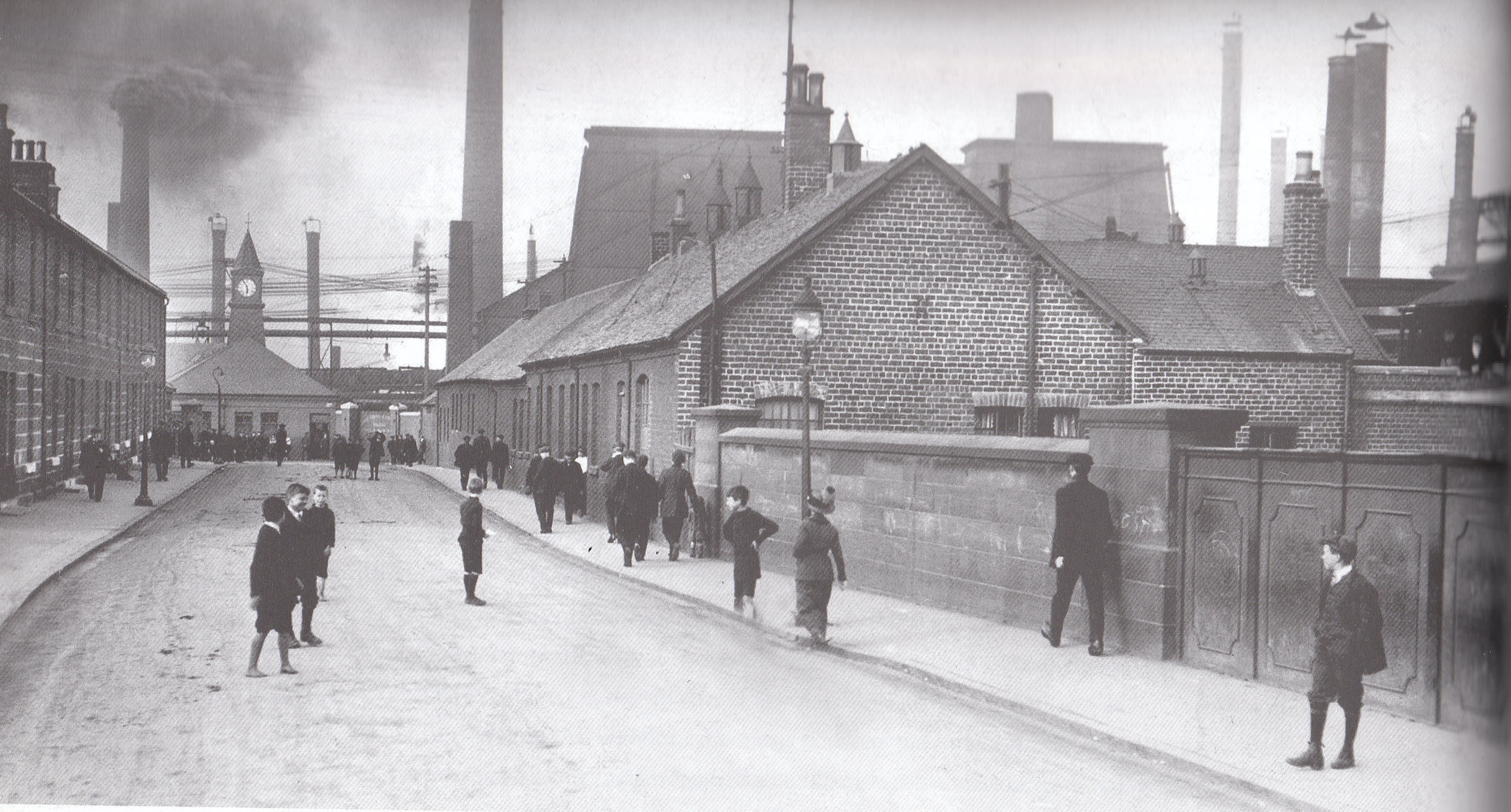

What’s missing is any sense of what it meant for the unluckiest. The term “smog” was coined by the campaigner Des Voeux after a catastrophic fog over Glasgow and Edinburgh in 1909, and that lacking sense is typical of writing from, and about, the period, all of which must choose from the comic, the outraged or the excessively dignified modes. The Scottish newspapers of the time opted for dignity: the fog of 1909 is reported as a lack of wind and loss of visibility, and the hindrance to trade as shipping found itself confined to harbour.

That fog lasted for mere days, but killed more than two thousand people. I am prone to asthma and bronchitis, and can feel this. The exhausting fight for breath; the escalating pain in your throat and lungs as cough after racking cough sands them raw; the scrapes and bruises as your body in constant spasm hits the wall and hits the furniture; the guilt and the rising panic. For two thousand people, there were not the medicines and inhalers that I had when it was at its worst, and this must have gone on and on, into pain and tiredness and fear that I can’t imagine, until it wore them out and killed them.

All this Des Voeux himself somehow reduced to inconvenience. In a letter to The Times in 1911 he wrote – and it really does start like this:

How long – oh, how long! – will the people of London continue to endure the murkiness and gloom of its winter months, the fogs that turn daylight into a darkness worse than night, and the dirt which penetrates into all houses and covers the rooms with a film of sticky filth which only arduous and continuous labour can remove?

(..)

As I write (at 2pm) we are in complete darkness, the whole house lighted artificially, the daylight being absolutely blotted out by a black cloud overhead, produced, not by a threatening storm, but by the smoke that has been formed from the fires that have cooked the Sunday luncheons or dinners of 6,000,000 million people.

(..)

At 8 o’clock this morning the air of St James’s Park was clear, by 9 darkness was coming on, and by 1 o’clock it was nearly complete. Sunday fog and darkness are always an hour later than week-day fog, thereby indicating their origin from the domestic hearth.

And with that, we move our attention to London, where with hindsight we know that the worst was already over by the time Des Voeux wrote his letter. Meteorological changes after the beginning of the twentieth century dialled the London Peculiar down somwhat, although we still don’t understand how or why. But in the 1880s, the London death rate could double during a bad fog, reaching levels only otherwise seen during an outbreak of infectious disease. No historian or author of fiction seeks to make local atmosphere out of cholera or smallpox, and their willingness to do so out of fog isn’t questioned as often as it might be. It’s hard to think of another instance where the example of Victorian and Edwardian writers is followed so slavishly. So many people’s relatively sudden and unheralded and violent, fearful deaths, you realize, get shoehorned into chapters about nuisance legislation and public health statistics.

Those people are harder to forget when you are suddenly nose-up to the soot in an unrestored Edinburgh mausoleum. The answer to what the hell did that? isn’t just “smoke”: it’s, “smoke: and this is the very least of it -” It would be comforting to think that the way people die from respiratory diseases is to slip away, quietly and painlessly, shelving themselves into neat statistics, a Blackadder Goes Forth kind of ending, tailored to the weak chested. But it isn’t like that. It isn’t like that at all, and what it’s really like is as much part and parcel of the Victorian and Edwardian experience as anything else, if too painful to contemplate.

“Meteorological changes after the beginning of the twentieth century dialled the London Peculiar down somwhat, although we still don’t understand how or why”: hurray for Global Warming.

Bjørn Lomborg in his The Skeptical Environmentalist remarks that air pollution in London was decreasing before the Clean Air Act and that the slope on the graph didn’t change when the Act came into effect. So a large contribution was presumably the change from coal to oil in industry. (London had a lot of industry then.)

I wonder, though, whether the Act was necessary to force householders away from coal – this was long before North Sea gas arrived.

P.S. My wife was in the last London smog, a cousin of mine in the last Edinburgh smog. But I am a country boy.

Ah, but I remember coming down from the desert in a Greyhound bus and looking at the photochemical smog over Los Angeles in 1966. Geeze!