The room was right out of a book and I began to say to myself I guess dreams do come true.. Because here I am, living in a Paris garret, writing poems and having champagne for breakfast (because champagne is what we had with our breakfast at the Grand Duc from the half-empty bottles left by unsuspecting guests. (Langston Hughes recalling 1924 in “The Big Sea” 1940)

A decade later, Hughes would become the first truly major jazz poet, but in 1924 in his Parisian attic, he was just one of a whole series of black American artists from every genre making his way abroad – and finding the Parisian way abroad rough, but also open, unprejudiced and accepting in a way America was never going to be.

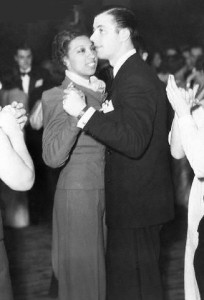

It was the musicians above all who crowded into Lower Montmartre and Kiki’s Montparnasse. Theirs is a huge story about youth and brilliance and struggle and release, too broad to be told in full here and still going on – see The Spirit of Black Paris for much more.

What we can reflect upon are the extraordinary before and after effects. Josphine Baker and Philip Larkin’s hero Sidney Bechet came over in 1925 with the Revue Negre. They had contrasting fortunes: the young Bechet had already seen the inside of a British gaol, and in Paris he contrived to be wounded in a shoot-out that, depending upon your witness, was either an ambush, or, more splendidly altogether, pistols at dawn. Bechet’s great Paris period would have to await the peace after World War II. But Josephine Baker thrived.

America had used Baker as little more than an end of chorus girl, the one last in the row who’d goof the routine before reprising an elaborated version of it superbly at the end. There were songs, too, of course; here, in What Do I Say After I’ve Said I’m Sorry? Â she’s the well-meaning public schoolgirl of the weeklies, petitioning her cricket captain beaux after some innocent misdemeanour:

There was a kind of fame in America, but what Paris gave her was the dignity due to her own naturally overwhelming presence. No longer the daffy rhythm bunny of jungle music, Baker was declared an artist in the fullest sense. (Paris would one day accord the same to the young Rolling Stones – always a French band, but stranded in Romford by accident of birth).

America’s Baker was given grass skirts and bananas: in Paris, she could take the geegaws or leave them, and the French photographs show her in elegant dress, wearing that brilliant hallmark smile. One can only imagine that this next song – J’ai Deux Amours -Â came from the heart:

1920s Paris is, of course, one of the great time machine destinations. The food, the art, Kiki and Man Ray, Atget’s city still standing and Brassai’s about to get underway. Picasso, Fitzgerald and Hemingway! and in Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris the elegant open-fronted cab draws up beside Owen Wilson one bland modern evening, eager passengers pull him inside and off he travels to see and meet them all until morning..

The musical backdrop to Owen Wilson’s enviable adventure is Cole Porter’s in part – and Porter himself turns up in the film, heartbreakingly young and fit in the years before the accident that crippled him. But above all, it’s Sidney Bechet’s. Bechet returned to Paris at the start of the 1950s, and for all that Larkin has Bechet referencing “New Orleans reflected on the water.. My Crescent City1“, it’s Paris Bechet really captured. Petite Fleur wasn’t recorded until 1952. But Paris in the golden era is right there inside it, and what better gift to give your welcoming home from home than that city’s own eternal signature tune?

Petite Fleur aside, Midnight in Paris ignores the black jazz emigres. Woody Allen’s tribute to them is elsewhere. It’s just as well. Owen Wilson’s trips back into the world of Hemingway and Fitzgerald treat the past as a room whose ornaments are splendid but static, and, despite Wilson’s eventual reconciliation with the world of 2010, there’s no doubt where the real sympathy lies: the past is better than the present. For the black artists of the 1920s, nostalgia was altogether more than they could afford, and their trajectory would take them far beyond it in time. They came to Paris not to be nostalgia’s pets, but to become its fierce opponents.

1Philip Larkin “For Sidney Bechet” The Whitsun Weddings 1964

It’s fascinating to see where Coleman Hawkins recorded then: London, Hilversum, Zurich, Laren, Paris, The Hague; others recorded in Copenhagen, Hamburg etc, etc.

The best track I have by the ODJB (a white band) was recorded in London; I also have London tracks from Duke and Fats.

And that’s with picking up just eight CDs.