It has always bewildered me that Great Western Trains – the private franchise running services from London to the West of England and Wales – has never availed itself of its astonishing aesthetic inheritance. Perhaps there are copyright issues – I don’t know, or they wanted to make their own modern mark. But at any rate they have seen fit to ignore the fact that they occupy the site of one of the triumphs of British industrial design, namely the Great Western Railway.

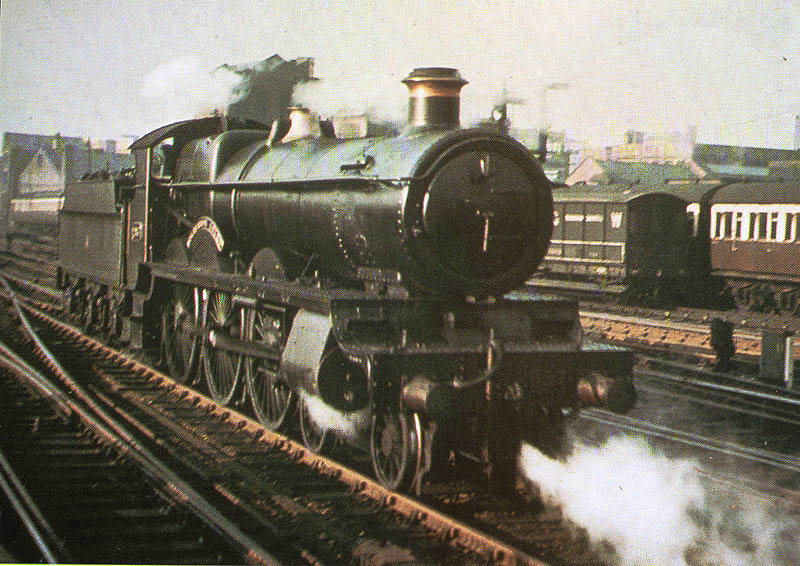

For sixty years, the Great Western Railway owned and promoted one of the most outstanding and successful “corporate images” of any private company. It’s not just the green and copper of their beautiful locomotives, or the tastebud torturing chocolate and cream coaches. It’s the design of station buildings, right down to posters and signage; it’s the uniforms, the plates and cutlery, the company iconography.

![paignton-south-devon-english-vintage-great-western-railways-travel-poster-print-642-p[ekm]288x201[ekm]](http://www.garreteer.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/paignton-south-devon-english-vintage-great-western-railways-travel-poster-print-642-pekm288x201ekm.jpg)

All of it was there for the taking when Great Western Trains was legislated into being in 1996. Perhaps, given their well-publicised difficulties, appropriating Great Western Railway design might have come to seem sacrilegious.

And even the Great Western Railway itself lost a little of its talent by the end: the company had kept at the forefront of both technology and design for sixty years (they were fitted out with advanced train warning systems 30 years before anyone else and their safety record was the best in the world by some margin). But after Chief Engineer Churchward’s premature retirement, and the departure of Felix Pole to AEI, the energy palpably slackened, the talented number two, Stanier, fled to the rival LMS, and by the time Hawksworth took over, war and the imminence of nationalization made everything else moot.

But you do get the feeling when looking at Great Western design that you are in the presence of the British industrial aesthetic at its absolute height. There is the same sense of culmination about it that you get when contemplating the Apollo Programme – of something outrageously successful that also looked magnificent and yet looked entirely itself.

For all that, the Great Western is badly served online these days. It’s the Southern Railway, not the GWR, that is hugely served with online prewar film, and the LMS and LNER who seem to have attracted prewar photographers with autochrome or Kodachrome film in their Leicas. The GWR had a busy film unit. Where are those films now? No one seems to know.

There is just this, from a minor prewar movie called “The Last Journey.” Brief, scratchy, black and white and with its attention on all the wrong things, it is like gazing out onto Bourton on the Water at night through a lace curtain. But it’ll have to do.

“war and the imminence of nationalization made everything else moot”: is that the American sense of “moot” you are using? By a chap from the Signet Library: I do hope not.

I refuse to take lessons in grammar from a cantab…