For children born in 1967 and 1968, it was simple. Before we were born, it was black and white. For the whole of our life, it’s been colour. Colour television, colour supplements, Kodacolor. We brought the whole spectrum with us. And in Britain, the debris of the black and white days was everywhere.

For me, aged five in 1974, it was hazily evident that something very bad had happened late in the black and white times. In our house, the best furniture was the oldest. The stately hardbound volumes on our bookshelf, not that there were many of them, were old, and the bashed-up paperbacks new. The early pages of the photo album showed people who dressed smartly and gave the impression that they knew what they were doing: latterly, the pictures were of felled elms and flaired trousers – that complete aesthetic break from any clothes the British had ever worn before.

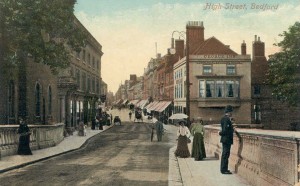

1974 was the year we bought Richard Wildman’s “Bygone Bedford”, which told the story of a beautiful market town on the river that helped win the war and then enviscerated itself. It was obvious even to me, looking at the world from a vantage point a ruler and a half from the ground, that the new buildings weren’t as nice as the old, and that the sharklike vehicles I saw on walks to the shop hadn’t always littered the pavements.

But I wouldn’t have thought of it in terms of architecture or national decline. These vague hunches drifted into me as gently as the breeze, and I saw them in the context of the music and stories that surrounded me in each of my childhood homes. My parents had split up and divorced just before I emerged into consciousness, and the wish for them to get back together was one of the few really sharp longings I knew, and the first I learned never to voice out loud. Those things that the children of divorce all share – the eggshells, the big chunk of your life that was never spoken of, guilt at the scorned and ridiculed love you still held for the other parent – were mine too. I had my deep instinctive understanding for myths of the Fall without any help from the Seventies.

But there was help from the Seventies, of course. The radio was quite consistent on this: the songs were about separation, endings, abandonment and mourning. Seasons in the Sun; Billy Don’t Be A Hero; Band on the Run; If You Leave Me Now; Please Don’t Go. I had a memory – a mere snatch of one; a young woman in a miniskirt bending over my pram, and coming from behind her, through her long hair, that astonishing 1960s sunshine in which everything was possible. That sunshine was on television – reruns, I now know, of the Monkees and Banana Splits. But I never saw it outside. It was that sunshine I connected with the radio’s wistful loneliness and my parents being together once and an unremembered but longed-for period of my life when my train set worked and my tricycle still pedalled forwards as well as backwards.

(The Monkees and Banana Splits told me something else, too, which I understood later but intuited then: I was in the wrong country. The future was sunny, colourful, optimistic, adventurous, zany and, above all, American. Or it had been, at least, in that time of my life I didn’t remember. But where was the future now? In jittery, unglamorous Weekend World, with its theme tune that sounded like a bacon slicer at Sainsburys?)

Five year olds have little sense of genre. I was aware of Westerns, and would have been aware of war films had I not believed, like all of my classmates, that we were still fighting Germany. But literature was a matter of books I could read and the ascending staircase of more difficult books which I was too young for. Music from the radio was just there: “music” was what we sang around the piano in hall. I don’t remember any poetry qua poetry, and as for paintings, sculpture –

Which is why some of the juxtapositions my imagination inflicted on quite unrelated pop singles and TV shows are so deep and yet so surreal. There was nothing to keep them apart. When Martin Amis divorced, the shocking pain of it took him aback. “Why didn’t literature warn me?” Well, literature didn’t warn me, either – and nor did the 1974 Planet of the Apes TV series or 10cc’s 1975 single “I’m Not In Love.” At least, they didn’t overtly, but my five year old mind was able to build an understanding by harvesting bits and pieces from them and from the first “Star Trek” series in ways that Google can’t quite piece back together.

Because somewhere in Apes and Trek there’s a scene where they stumble upon the last records of a lost civilization – I remember something about discs like spinning plates. And the sense of loss and distance and hopelessness that started in me found somehow that it had to do with the hot grassland raga that follows the whispered “Big Boys Don’t Cry” (such useful advice for a 5 year old) in “I’m Not In Love” – an idea of what being utterly alone and abandoned would be like, as Heaney said of “lunar distances/Travelled beyond love.” 1

1Seamus Heaney Wintering Out (1972)

It’s nice to think that Bedford once wasn’t a dump. The only common reference to Bedford that I’ve heard in Cambridge is along the lines of “If you do that you’ll end up in Bedford jail”.

I can remember essentially nothing about being five. I went to a school reunion once and was struck that some of my old pals could remember events in my life at Nursery School that I couldn’t. Struck but not surprised – I’ve always had a lousy memory.