You don’t get to choose the books you learn to read from, but they can stay with you for life. I was given the basics elsewhere, but once I knew the ropes, the Reverend W. Awdrey’s “Railway Series†set me properly on my way.

You may not have met these. You will have if you’ve had children in the last twenty years, because there’s a televised tie-in, “Thomas the Tank Engineâ€, and the books have become all but ubiquitous amongst young readers, retro training camps for the forthcoming attempt on Harry Potter. The Series is about an imaginary island called Sodor and its railway system, run by a team of locomotives who (living and feeling beings themselves) work under the benign dictatorship of a transport bureaucrat nicknamed “The Fat Controller.â€

The Series had its somewhat unsatisfactory early publishing success in the 1940s (Book 3, “James the Red Engineâ€, announces that Sodor, like the other British railway companies, had been nationalized), but Awdry had soon created a thoroughly likeable and psychologically coherent world, and would continue with some quite excellent storytelling until just before the Yom Kippur War.

For books aimed at such young children, the characters are strong and develop well: the fragile, narcissistic Henry, the gentle, unselfish but uncrossable Edward and Toby, Rheneas, brave to the end, the aristocratic, unflappable but unimpressable Duke. Only Thomas fails as a character, and that it is he of all of them that came not just to headline the TV series but to encapsulate something for the British about railways altogether – this is something that can only make the genuine lover of the books writhe in discomfort.

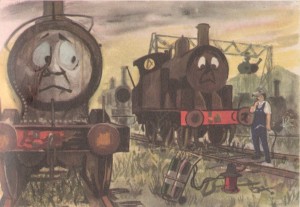

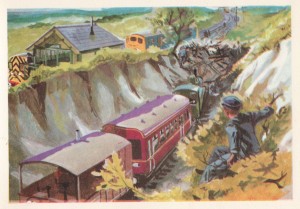

Awdry built a fictional world as rich and memorable as Wodehouse’s, but unlike Wodehouse, it doesn’t pull its punches. Like the BBC’s Springwatch, et in arcadia ego. Godred falls to his death from the Culdee Mountain Railway’s trickiest, most dangerous spot. Engines with faces on them are scrapped – and we see them eyeing the acetyline torch that will, in moments, tear them to pieces. At least one human character is portrayed bedridden with a serious illness she cannot afford to seek treatment for. Final, crushing defeat is a reality – lines close, and are lifted, and disappear forever as nature reclaims the land. Sodor is prey to crime and personal weaknesses: boys stone trains from bridges. A good half of the stories engage with greed, arrogance and the effects of narcissism, dishonesty and gossip.

To this young reader of the railway books, the impression was of an ordered, meaningful world, one in which endeavour, courage and decency were paramount virtues. It was a world view I took on in full. Every divorced family is chaotic in its own way, and the underlying Anglican calm and structure of Awdry’s world was highly attractive to me, an almost hurtful contrast with my day-to-day reality.

The books track the Sodor railway system’s shift, from a modern everyday operation like any other, to a besieged museum piece, the haunt of outsiders, survivors and eccentrics. One of the big themes of the books is the post-War struggle of railways. Duke’s line closes. So does Toby’s. Skarloey’s survives only by the skin of its teeth, and young readers are presented with the issues face on, as ageing locomotives struggle home on overgrown tracks with dwindling passengers.

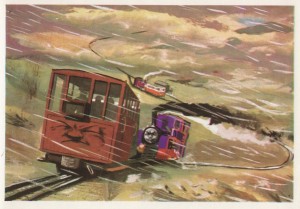

At first, the threat is from other modes of transport. This is reflected in the series of race stories – Percy against Harold the Helicopter, Thomas versus Bertie the Bus. Bertie proves to be made of the right stuff, but other buses don’t: Bulgy steals passengers, but proves unreliable in every way, and mean, and ends up a henhouse in a field. But later on, the focus of battle shifts: it’s diesel versus steam, and steam’s defeat – despite its ability to struggle home on one cylinder – is what ultimately condemns Sodor’s railways to unseriousness.

This is reflected in the repeated arrivals, from “Edward the Blue Engine†on in the Series, of the cavalry in the form of a pair of deus ex machina called the Thin And Fat Clergymen. The Thin Clergyman is Awdry himself, who was in real life engaged in railway preservation from its 1952 beginnings on the Talyllyn Railway. The Fat Clergyman is a version of his real life friend Teddy Boston. Boston, like his alter ego in “Duke The Lost Engineâ€, did indeed find an abandoned locomotive in a forgotten shed, and did save a doomed traction engine from the torch (Trevor in “Edward the Blue Engineâ€). Here’s Boston at home. It gives the flavour:

Awdry’s was a world in retreat, then, in retreat moreover from the very world into which I was emerging. Something settled and safe and satisfying was being pushed out by a newer world that was aesthetically and morally inferior. An Anglican universe of hard work, good fellowship, mild-mannered English deities and the chance to recover from your mistakes, to earn redemption and the respect of your peers, was being cut into by something undesirable and unstoppable.

It was almost as if Britain had it in, in some way, for everything that had been implicated in the Great Depression and the two world wars which bookended it. A sense of “enough of all that†prevailed, and the demolitions and the closures and the denigration began.

And with it began that enduring and unspoken middle class contempt for railways which goes deeper than resentment over delays, cancellations and rising fares. Today, the possession of genuine technical knowledge about railways is considered comic and risible. Journalists and writers who venture onto this territory are careful to descend into the kind of language used by adults who are bad with children: trains “chuffâ€; the CEO of a railco is head of “the nation’s train setâ€.

And it was all better in the past. Learning to read with the Railway Series made me as guilty of that as anyone else. I assumed that the past had been something like Sodor, and so into the past I projected what I wanted but didn’t have: security, safety, order and trust. This, it turns out, is the British way. Just as British was my belief that all of those good things were lost along with the past: that it was no good trying to find ways to make them happen for ourselves now.

In the last of his contributions to the Series, Awdry cements all this by drifting into open satire, answering the new order’s heartlessness with heartlessness about the new order. The diesels who are taking over everywhere break down constantly, behave badly, are “sent away†(one of the heavier penalties in the Sodor universe). Awdry didn’t live to see it, but those diesels lasted longer in service than his beloved steam locomotives, and grew their own following in time.

But that, ultimately, is the British approach to life. Nostalgia for the past, satire for the present.

Is anyone happy with our railways now? With our transport, our housing, our cities, our children? What has happened to our real railways in the wake of their journey from seriousness to derision, to our transport, housing, our cities, our children, calls into question this whole schema, calls into question the utility of a culture so ridden with nostalgia and satire, especially satire when it is used, as the British have used it, as a substitute for the proper identification and analysis of real-world problems.

Of course, the high status of satire in out culture (highlighted recently in the evisceration of BBC4 as comedy-and-satire channel BBC3 is left untouched) has its advantages. Satire removes blame from the individual and pushes it onto the person or institution satirized. It takes away our responsibility for the state of things – which after all is someone else’s fault – and gives us self-righteousness and a veneer of intelligence instead. We might not achieve anything, but we won’t be fooled again. But for identifying, solving and powering past real problems – it’s not a really useful engine.

I remember enjoying these as a child, but nothing much about their contents. But then I can’t remember when or where I learnt to read either. I can remember my mother’s penetrating literary criticism, but I was 14 before she offered it.

The Railway Series – The best book series ever made.

The humour. For example:

“I don’t want to be a moving picture in a book”- Tit for Tat, Small Railway Engines

“Is that a train?” – Mavis and the lorry, Toby, Trucks and Trouble

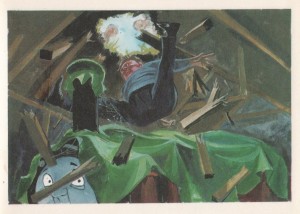

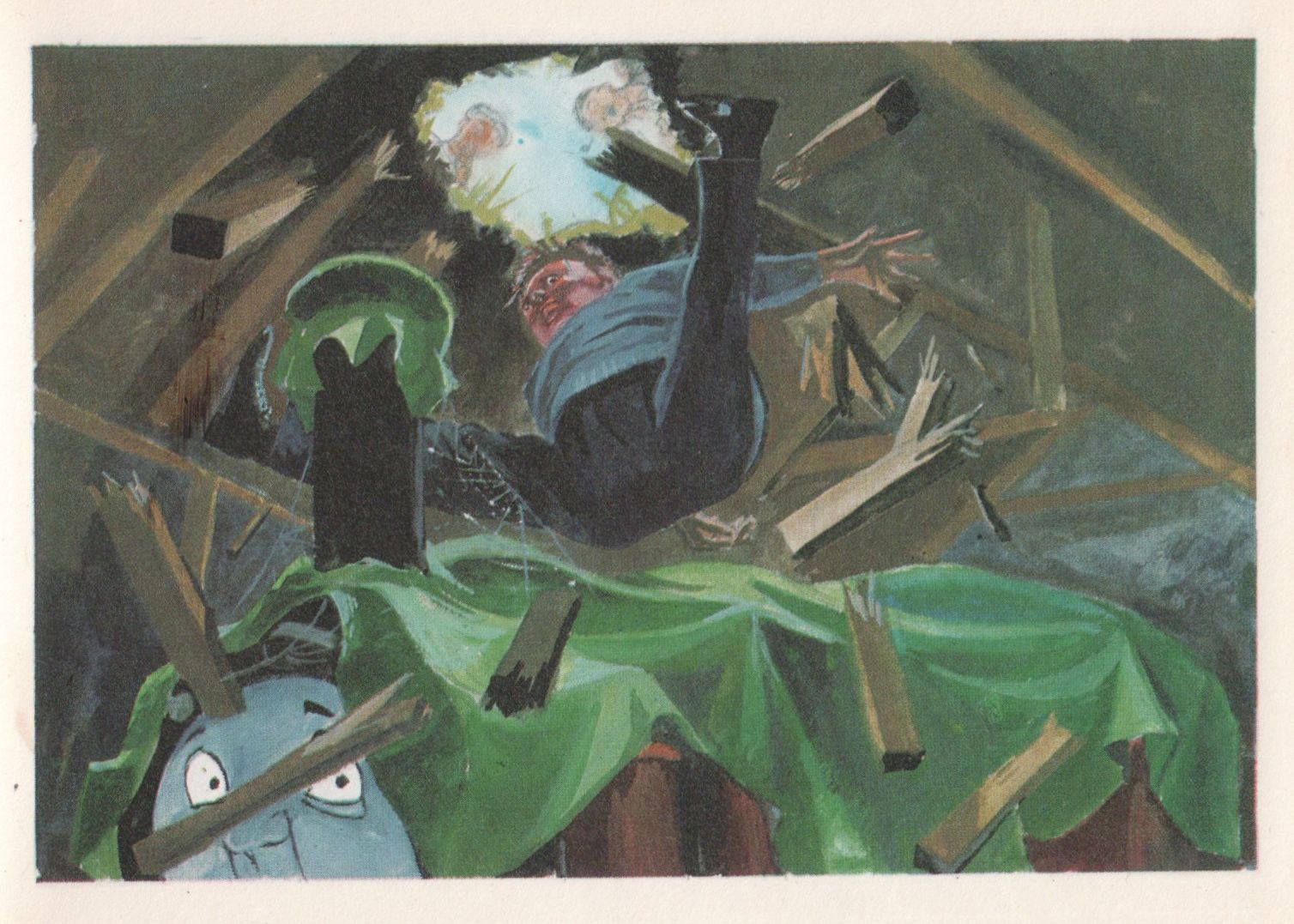

The pictures

Have you ever seen one of the pictures? They are fascinating!

The railways

The island’s railways are very complex. For example, Rev. W. Awdry made both a map and some timetables. The engines have different jobs, some take goods, some takes passengers. It has branches, sheds, several mines… Well, enough to have a real railway.

The stories

The stories is fantastical! They speak for themselves.

The hope

In “Enterprising Engines”, Oliver has a big hope he would get to Sodor. Despite having not that much coal, he try hard to struggle to the island.