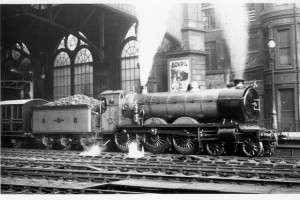

It was one of those changes that made the modern world: the arrival, in the middle of the 1890s, of fast photographic emulsions. And the reaction was immediate: the next five years heralded the Kodak box camera, the back page football action shot, cinema! and, not least of all, amateur railway photographers taking pictures of moving trains. They were just in time to capture the end of Brunel’s doomed, magnificent broad gauge Great Western.

In many ways, the pioneer railway photographers were classic Garreteers: obscure, spare-time makers of the best of things. None of them were wealthy men, but worked at a time when both photography and travel cost much more than they do now. H. Gordon Tidey was an estate agent; H.C. Casserly clerked for an insurance firm; Ken Nunn was an accountant for the Great Eastern Railway. Wodehouse would have dealt them foolish, undignified walk-on parts: flappers’ fathers from outer suburbia, slow-witted lounge bar golfers unburdened by vim or style. But like Wodehouse, they have left their legacy.

It’s a hidden legacy. The British use history – and railways – for comic purposes and nostalgia: therein wait people in funny clothes who knew community and proper values and chuff-chuffs. It’s difficult for the modern British imagination to capture the sense that these photographers and their contemporaries were, like us, living on the edge of history in a uncertain world. That classic phrase, “it was a gentler more innocent time” is a patronising way to look at periods of astonishing upheaval, population growth and technological change, at least at first sight. The wrenching novelty and extreme physicality of that world is almost lost – perhaps only Andrew Martin’s extraordinary “Jim Stringer, Steam Detective” novels (N.B. affiliate link)come close to its sounds, smells and ethos. But Britain has nostalgia where other nations have dreams of the future: what we want one day to have, we locate in our history. It’s a symptom of our ancestor’s success: when a society’s real problems have been solved, that society finds dreams of the future more difficult.

The early railway photographers were not artists in that mitteleuropa Brassai/Capa/Magnum Agency way. But because they were innovators, their images upset photography’s existing aesthetics and conventions, as did candid amateur snapshots and the first attempts at moving film. (Railway photography quickly created its own convention – the classic three-quarters railway shot, still the most common today). As with snapshots, there is unwitting unintended interest in these photographs – the accidental capture becomes more interesting than the intended subject. What wasn’t noticed at the time takes centre stage. It’s what lurks in the background. The Garreteer lesson is photograph the boring and the everyday and the taken for granted now: a century from now, historians will be grateful for it. These early railway photographs are no longer always about what you see in the foreground. It’s not something the men behind the lens would have expected. But this is what we owe to them.