In one sense it’s a mystery how something as cheap and reliable as the disposable ballpoint pen has not become a major medium in art. After all, it’s not because the ink is indelible, although it is. It shares that with all inks, and with silverpoint besides. And it’s not because the line is boring, incapable of registering pressure or emotion. A biro can be feathered across paper, or driven into it with passion, and all stops inbetween. Nor is it because the line’s width can’t be varied: this is also true of silverpoint, and, by and large, of pencil. It’s none of those things.

The truth is, the biro probably came too late. The British patent wasn’t placed until 1938, when the Biro brothers were living and working in Nazi Germany. The biro, like the mass-market highbrow paperback book, was one of those pre-War antecedents of the future World War II kicked into twenty years of long, bloody, impoverished grass. And by the time the dust had settled, and real life brought back underway in the West, mainstream art had moved away, with a kind of concrete finality, from the representative basis that might have been the foundations of art in biro.

When representative art became the stuff of backwater, reaction and conservatism, biro was too new to be taken on board. And when representation of sorts returned, there were newer, more exciting media – film, video. Biro was just never around at the right time or the right place and never became established in the art supply, art medium pantheon.

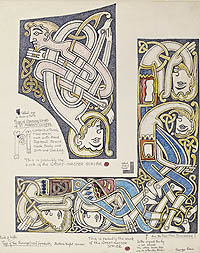

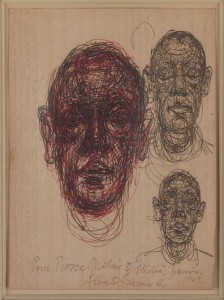

There are the odd exceptions as there always are. Giacometti appreciated the speed, the fluidity and smoothness and reliability of the biro, the way you could swoop about with it on any paper for extended periods without pause for as long as you chose, without refilling or the lead blunting or the nib biting a hole in the paper. George Bain, the Scotsman who did so much to revive the art of celtic calligraphy and illumination, made brilliant use of coloured biros in creating teaching aids. More recently, Leeds artist Mark Powell has used biro in a series of remarkable portraits.

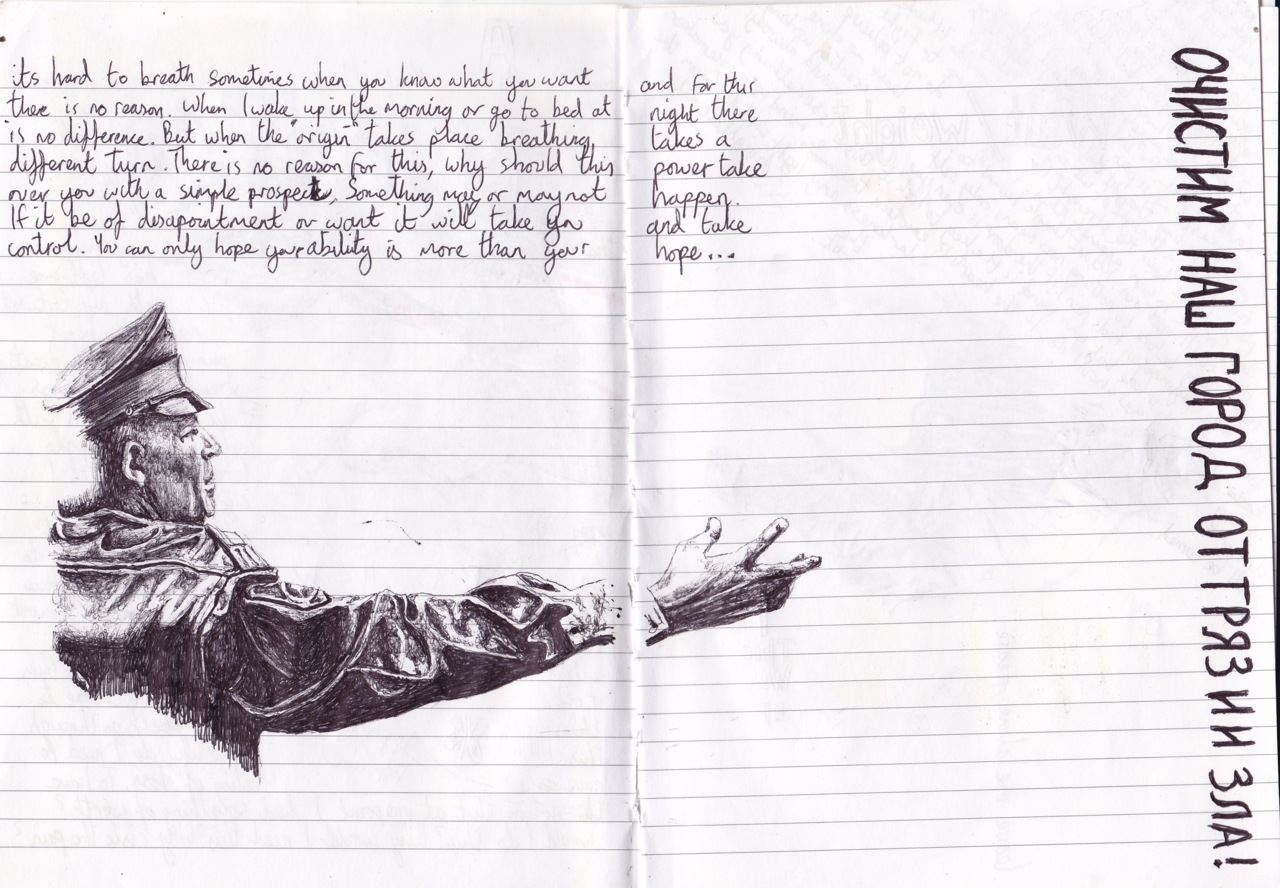

But for the most part, drawing in biro remains provincial: it happens in artists’ notebooks when they’ve nothing to hand at the airport or concert. It’s the doodling medium. It’s the choice of savants on the bus who biro astonishing imaginary landscapes in the margins of free newspapers, their hand bobbing in that irresistable rhythm that only real artists know, before dropping the paper into a bin at the bus stop.

This is sad, seventy years on. But it does mean that there’s an opening there for a Garreteer artist who cares to take it on. The question is, who will follow Mark Powell into this cheap, always accessible, reliable, multicoloured medium and do something with it that will surprise the world? And do it, moreover, in collaboration with other neglected, unsuitable, cheap and reliable media – newspaper, A4 lined refill pads, post-it notes, the backs of letters…