“Stopping the diary”, wrote Philip Larkin, “Was a stun to memory/Was a blank starting”(1), and for the British at least, World War II performed the same function. It brought a great forgetting down, and now the world before it is a blank starting, a home for every dream for the future that the British hold, hopes expressed only as nostalgia. The clean uncommercial community the British long for is meant to be found there, in all the pre-War places from where so few survive to tell a different tale.

But the dream was just the same then – in 1914, Rupert Brooke could write (2)

To turn, as swimmers into cleanness leaping,

Glad from a world grown old and cold and weary,

Leave the sick hearts that honour would not move,

And half-men and their dirty songs and dreary…

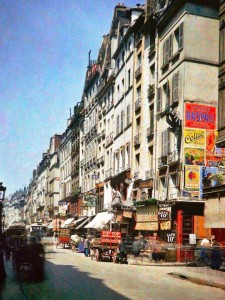

And a world ungoverned by commerce? The nascent trade unions would not have agreed: and then there’s this autochrome of a Paris street in 1914 –

The career of the young Cab Calloway is in itself a reminder that when the British place their hopes for the future into nostalgia for the past, they put it in the wrong place. Calloway was the middle class product of business himself – he was the son of a commercial lawyer who would not be reconciled to his taking to the musical stage.

We met Calloway in an earlier post about the 1943 film Stormy Weather. In Stormy Weather is the whole of twentieth century music, reprised or superbly presaged, and in it Cab Calloway stands as the ultimate charismatic front man and lead singer.

Calloway’s band spent the early 1930s alternating with Duke Ellington at the Cotton Club in New York, and, like Ellington, the Club made Calloway an early and groundbreaking star of radio. Through radio, Cab Calloway began to be cast in cinematic advertising shorts like the one below for Homefire Radio. The Homefire Radio short shows him and his band on tour. It’s the sheer industrial physicality of the steam railroad that impresses first – that all this, and all that went with it, were once the leading edge of history for someone, the present, taken for granted but now vanished beneath countless tiny changes accumulating over time. But then the ad takes over. And it’s a strange one! Swaggering onstage sexuality in 1933 from Calloway leads to an ordinary working man being cuckolded by the big stage star, and all with the help of the radio that the ad is supposed to be selling…

Of course, the shadow of the Hays Code hangs over all of this, and over another Calloway film now, a Betty Boop Talkatoon from the previous year, 1932. For a Boop toon, this is surprisingly close to the bone – grief and fear and horror predominate, arranged around the performance of Minnie the Moocher that would become the Calloway callsign. The Walrus – forty-five years before John Lennon – is the cartoon’s take on Calloway’s “buzz” Jackson-moonwalk-gazumping stage dance done via a pioneering use of rotoscoping:

This is sex before 1963 again, and Calloway’s ultimate expression of that which Presley, the Beatles and Stones are alleged to have engendered came ten years later. Calloway is just terrifying here in Geechy Joe (from Stormy Weather again) – Elvis, Michael Jackson and the entirety of hiphop all roled into one magnified and – in the real sense of the word – appalling whole:

(1) Forget What Did High Windows 1974

(2) Peace 1914 and Other Poems 1915

One doesn’t really need to have discovered jazz to decide that most popcrap and rockshite is dreadfully poor stuff. But it certainly drives the lesson home: it’s not just rubbish compared to yer Mozart and yer Beethoven, it’s rubbish judged by its own lights.